THE LATER YEARS: ROTARY ENGINES IN THE 20TH CENTURY.

With the introduction and development of the steam turbine, which could be regarded as the apotheosis- or more likely the nemesis- of rotary steam engines, the impetus behind the development of positive-displacement rotary engines must have been much reduced, but it did not disappear. The technology appears so seductive that it appears that people will be trying to come up with a workable rotary steam engine until the sun cools. Certainly the patents on rotary engines did not stop coming. See here for some later patents in Britain and the USA.

THE OGDEN ROTARY ENGINE: 1918

|

| Left: The Ogden engine: 1918

Minor matters like the First World War did not stop the flow of rotary engine designs.

The Ogden engine had a two-lobed rotor keyed to a hollow central shaft. Three rotating valves (marked 3 in Fig 3 of the diagram) were rotated by spur gears from the central shaft so as to clear the way for the rotor lobes just in time. Admission and exhaust of steam was through the central shaft which had ports cut into it. The handle 19 was a combined throttle and reversing lever, reversing being accomplished by sliding the shaft with the valve ports.

It is always worthwhile inspecting the text of a patent to see if there are any clues as to whether the design was actually built. For example, the patent text for the The Hodges Engine of 1885 contains convincing indications that Mr Hodges had practical (and disappointing) experiences with rotary engines. As for Mr Ogden, he says at one point "Experience has demonstrated that the organization above described is a highly efficient one" but I suspect that was pure bluff.

Neither Mr Ogden nor his engine are known to Google.

From US patent 1,269,735 granted 18 June 1918

|

THE JOHNSON ROTARY ENGINE: 1921

|

| Left: The Johnson engine

Rotary engine kept on coming in the Roaring Twenties. This design, by Albert Johnson of Minnesota, has two so-called valves G that interface with the main rotor D and seal it. To make this work they are driven at a variable speed by an elliptical gear on the main shaft; I would have though that would require some very precise kinematics to get anything like a seal.

Since the segments G do not appear to cover the inlet ports F at any point in their rotation it is hard to see how they can be called valves. According to the text there is an attached control disc J which actually opens or covers the inlet ports, but this is not shown on the drawing to the left. The exhaust ports are labelled E.

From Proceedings by the United States Naval Institute, Volume 48 Part 1, May 1922, pages 840-842

|

|

| Left: The Johnson engine animated

Another brilliant animation by Bill Todd. The bizarre elliptical gears can be seen in ghostly white outline. The movement of the disc controlling steam admission can just be seen in the white slot under the right-hand valve.

Note that Bill has had to remove the hook-like protrusions on the piston in order to make it work at all. This strongly suggests that Mr Johnson never built his engine.

|

|

| Left: The Johnson engine described

But no news as to whether it was actually built or not.

A little research shows that the US patent granted to Albert Johnson was No 1,389,874 on 6th September 1921.

From Proceedings by the United States Naval Institute, Volume 48 Part 1, May 1922, pages 840-842

|

THE CHAPMAN ORBITAL ENGINE: 1973

Originator: Howard R Chapman (California, USA)

This engine was a "steam engine" powered by Freon. It was intended as part of a bottoming cycle to improve the efficiency of conventional IC engines.

|

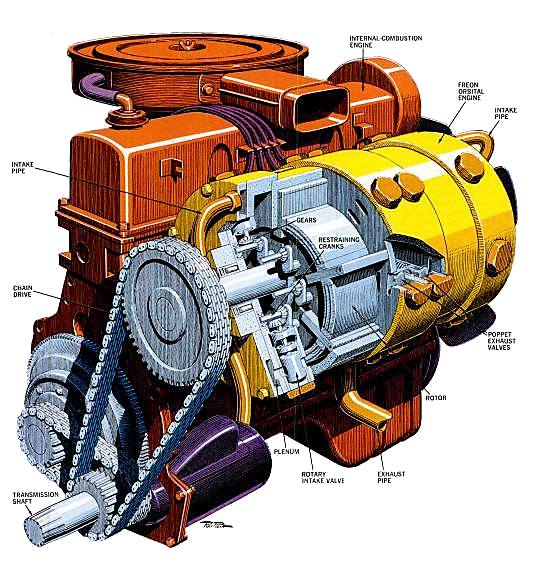

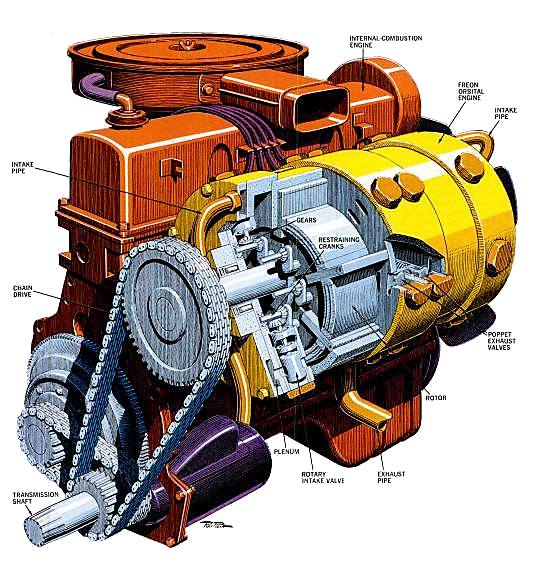

Above: The Chapman engine attached to a conventional IC engine. The eccentric rotor does not rotate; radial sliding seals create six working chambers.

Inlet and exhaust are by multiple valves not shown here. The six things with a star at one end are the cranks that restrain the rotor from rotating; the stars represent the bevel gears that drive the rotary inlet valves- see picture just below. Each seal only wiped a small part of the periphery. They were pressed against the inside of the casing by compression springs.

Image from Popular Science, Jan 1976

|

|

| Left: The Chapman engine mounted on its host internal-combustion engine, and coupled by chains to the output shaft. Note that the relatively low-speed Chapman engine needs to be geared up to match the IC engine output rpm.

Freon vapour is admitted by rotary valves, and leaves by poppet exhaust valves. The former were driven by gears on the multiple cranks restraining the rotor. How the exhaust valves were actuated is not known.

Image from Popular Science, Jan 1976

|

|

| Left: The Chapman engine in its bottoming cycle.

Three hot fluids- engine cooling water, lubricating oil, and the exhaust gases- pass through the boiler (heat exchanger A) and boil the Freon. This generates power as it expands in the Chapman engine. The Freon is then condensed in heat exchanger B by the engine cooling water that has just left the radiator.

Image from Popular Science, Jan 1976

|

Unlike some bottoming-cycle projects, the Chapman operation received no government funding. Its history is currently unknown, but it is clear that Chapman did not make thing easy for himself by attemping to make a satisfactory rotary engine at the same time as exploring the novelty of automotive bottoming cycles. At least one other bottoming-cycle project, by Thermo Electron, (which did receive government funding) used a three-stage turbine running at 60,000 rpm.

See United States Patent 3,743,451, "Rotary Engine", published 1973

This engine should not be confused with The Chapman Engine of 1810.

THE HENRY ENGINE: 2000.

|

| Left: The internals of the Henry engine. Reproduced by permission.

The Henry engine is mainly aimed at exhaust heat recovery from combustion engines, ie a bottoming cycle.

The aims of the Henry Works are:

- An engine with a higher efficiency than turbines of the same power rating.

- A design which is less expensive to produce than a turbine.

- Similar smooth running characteristics as a turbine.

- A simple design which is easy to repair or service in the field.

- Ability to handle wet steam due to its robust parts and slower speeds (3000 RPM).

- Higher efficiency over much of its RPM range making speed control less critical than in turbines.

See The Henry Engine. (External link)

|

And now... some unique pictures of the Henry rotary engine prototype undergoing testing.

|

| Left: First run of the P-4 Henry engine in January 2000.

Personnel: Mike Taggett, George Gubler and Merrill Harker.

Reproduced by permission

|

|

| Left: Early field tests of the Henry engine at a boiler company in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Reproduced by permission.

|

|

| Left: Mike Taggett with "Henry P-4" installed at an Ethanol plant in Minnesota.

The engine is powering a 7 HP pump. P-4 accumulated 250 running hours here in January, 2003.

Reproduced by permission.

|

Update from Mike Tagett, April 2011:

"My engine work has been on hold for a while until we can improve efficiency... we did operate an engine at an ethanol plant some years ago for 2 weeks at 150 psia...efficiency pretty poor...about 45 lbs/hp/hr We made good progress with sealing material though..."

"A rotary steam is such a simple but difficult problem... I do think getting to piston type efficiencies (70% isentropic?) is possible with the right engine materials, flow characteristics, seal materials and valving... I hate seeing poppet valves on a rotary but they do work well it just defeats the overall purpose of smooth rotary action. I think there could be an application in the 5-100KW range for a combined heat and power system (co-gen). steam quality and water quality become issues too."

THE LYNX ENGINE: 2009

Perhaps surprisingly, Youtube is a fruitful source of unconventional engine videos. Here is the Lynx engine, uploaded to YouTube in September 2009:

|

| Left: The Lynx engine being prepared for steam test

The Lynx Engine video

This engine is one of those most unpromising designs with a vane or flap (the white thing at the bottom of the cylinder) that bashes back and forth as the engine rotates. It is shown working from live steam, but apparently it sometimes needs a push to start. The rotational speed is only about 100 rpm.

Steam comes in at the left through the armoured hose, entering the cylinder through ports under the flap. The exhaust ports are at the bottom of the cylinder just to the right of the flap, and the exhaust leaves via the brass pipe going off to the right.

There is another video; a "high-speed" steam test of the Lynx Engine. Doesn't seem to be going round that fast to me; you can clearly hear the flap rattling. It's not a strobe effect as the steam is moving normally.

This seems to be the relevant website: Lynx Steam Engines. As of July 2017 the website has disappeared, but the two YouTube videos are still there. I think we will hear no more of the Lynx engine.

|

THE QUADRUM ENGINE: 2010

One of the problems of the rotary steam engine is finding a use for it. They're not going to be replacing the superbly efficient and reliable turbines in our power stations, and steam cars are not going to make a comeback. For most requirements for rotary power, you just specify an electric motor; and electric motors are pretty sophisticated these days.

Over the last few years it has occurred to several people that there might be a niche application in Combined Heat and Power. CHP typically runs a conventional IC engine on diesel or biomass producer gas, turning an alternator to generate electricity, and using the hot water from the IC engine cooling circuit and exhaust gases for central heating. However you can also burn wood to create steam in a boiler, use a rotary steam engine to drive the alternator, and use the condensate and boiler flue gases for heating.

You have probably spotted the snag; you need an extra component- the boiler. Certainly a successful rotary steam engine would be simpler than an IC engine, but a steam boiler is a serious piece of engineering that needs skilled maintenance and safety certification. Nevertheless the idea has had recent promoters such as Quadrum.

|

| Left: The Quadrum engine in 2010

Quadrum is a Finnish company. It calls its engine a Steam Motor.

The engine is one of the select few that have actually been built and tested. See the video on the Quadrum blog page. (Last updated in May 2016) I have dated the engine from the year of its first successful test run, on 9th August 2010.

|

|

| Left: Inside the Quadrum engine

The square rotor moves eccentrically inside a three-lobed cylinder, with its rotation controlled by the gearing. This is reminiscent of the Cooley engine

More picture of the engine and its associated boiler can be seen here.

|

THE SMALLENERGY ENGINE: 2013

The SmallEnergy Rotary Vane Engine has also been built and tested.

|

| Left: Three versions of the SmallEnergy engine

The basic principle is two vanes in a cylinder, moving so that the spaces between them expand and contract. This is reminiscent of the Stocker engine and the McEwan Ross "Rota" engine. Exactly how these vanes move is unclear, but apparently involves non-circular gears, which is not the first time these have appeared in the rotary engine story.

A PDF giving more information can be seen here. It appears to be the only info available via Google.

|

ROTARY STEAM ENGINES ON YOUTUBE

Getting back to Youtube, here is a small sample of the rotary steam engines displayed.

|

| Left: The Maguire engine on steam test: uploaded to YouTube in 2013

This engine was designed and built by Don Maguire.

You can see the video here. A speed of 2700 rpm was reached at 80 psi steam pressure. Steam can be seen blowing out of the right-hand bearing; according to Mr Maguire, this test was done with no seals fitted, and I have to wonder why. It is noisy, apparently due to the sudden release of exhaust steam that is still under significant pressure.

|

|

| Left: The Maguire engine internals: uploaded to YouTube in 2010

A still from an earlier video shows the inside of the engine.

The principle is essentially the same as that of the Eve engine of 1825.

|

The rotary engines I have seen on YouTube generally have two things in common:

- Firstly they are very noisy, which would seem to suggest poor kinematics with parts bashing into each other.

- Secondly, they are shrouded in clouds of steam when operating, indicating poor sealing and inevitable inefficiency.

This is the end of the historical section of the Rotary Steam Engine wing. Go back to The Rotary Steam Engine Index for more general information.